Perhaps, when stuck in traffic, everyone has wondered: “Why doesn’t the government just widen the road to ease congestion?” On the surface, that sounds entirely logical — a wider road should allow more vehicles to move, and therefore, no more traffic jams. Unfortunately, things aren’t that simple.

The Urban Planning Paradox: Building More Roads Doesn’t Solve Traffic Jams

Decades of transportation data in the United States have shown that expanding and building more roads does not improve congestion. A well-known example is the Los Angeles I-405 freeway expansion project in 2014, which cost over USD 1 billion and took five years to complete. “But the data later showed that the average speed on I-405 actually became slower than before,” said Matthew Turner, an economist at Brown University.

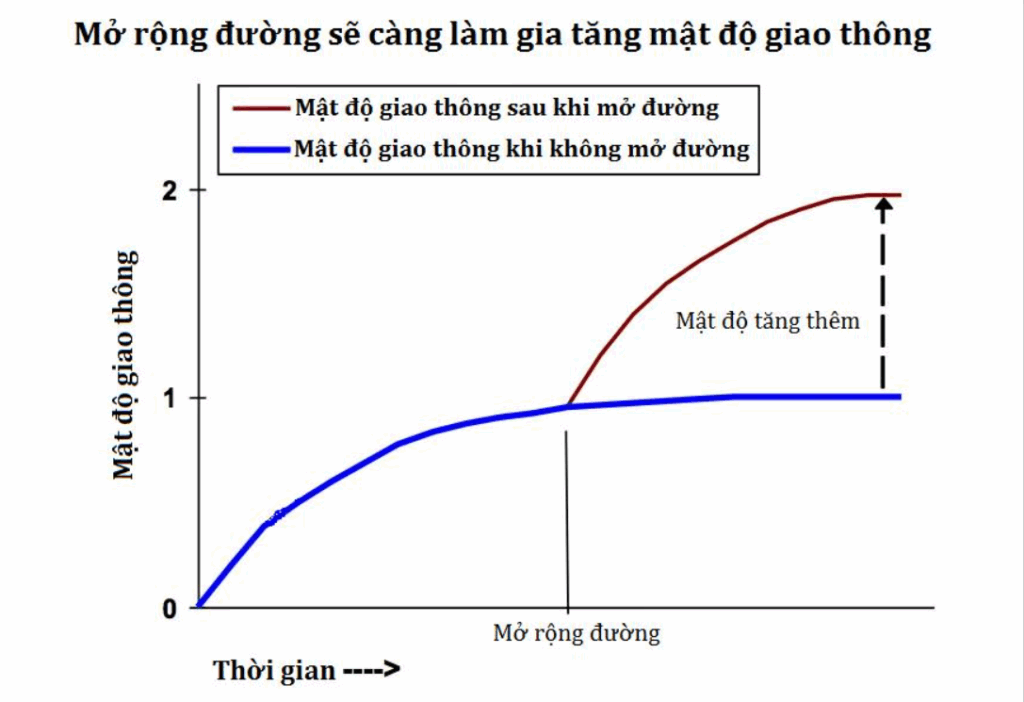

Turner explained that this puzzling phenomenon has a simple reason — expanding and improving roads stimulates travel demand. People begin to travel more frequently and over longer distances than before, leading to even more congestion.

Turner and his colleague Gilles Duranton from the University of Pennsylvania call this the “Fundamental Law of Road Congestion”: increasing road capacity simultaneously induces more traffic.

This paradox applies to nearly every country, mainly because drivers are not charged for road usage. When a valuable resource is provided free of charge, the demand for it inevitably rises.

Furthermore, Turner and Duranton proposed a hypothesis:

“The higher the road capacity, the greater the vehicle-kilometers traveled on that road — in direct proportion.”

For example, if the government increases a road’s capacity by 10%, the total distance traveled on that road will also increase by 10%.

Though counterintuitive, U.S. national highway data from 1983 to 2003 perfectly aligns with this hypothesis. Similarly, data from Japan, Spain, and the United Kingdom confirm the same trend: whenever governments expand road capacity, total travel distances rise proportionally.

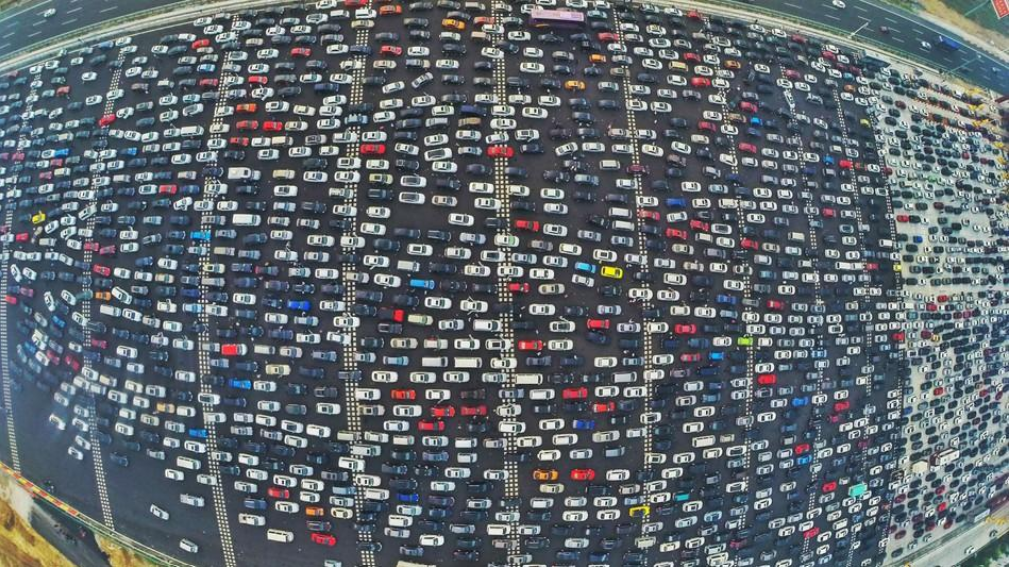

In China, for instance, the government upgraded its highway system from 16,300 km in 2000 to 70,000 km in 2010. Yet, by 2013, the average commuting time in Beijing had increased from 1 hour 30 minutes to 1 hour 55 minutes compared with the previous year.

An Everyday Example

Imagine there’s a store that sells a product USD 10 cheaper than the shop near your house, but it’s located 10 kilometers away. If you know the road to that shop is always congested — taking you over an hour — you’ll likely buy from the nearby store. However, if the road were smooth and clear, you’d probably make the longer trip to save the money.

This illustrates how improving roads increases travel demand, as people adjust their behavior based on convenience.

Why Public Transportation Alone Won’t Solve It

Turner and Duranton also found that promoting public transportation cannot fully eliminate congestion. Even if a portion of commuters switch from private cars to buses or trains, the newly freed-up road space quickly attracts new drivers, offsetting any temporary relief.

The Only Proven Solution: Road Pricing (Congestion Charging)

According to Turner, the only effective method to reduce traffic congestion is road pricing — charging vehicles for road use, especially during peak hours.

Under this model, the government imposes a toll on vehicles traveling during high-demand periods. In major cities like London, Stockholm, Singapore, and Milan, congestion charging systems have shown positive results.

For example, in central London, areas marked as “Congestion Charging Zones” require vehicles to pay £11.50 per day to enter between 07:00 and 18:00, Monday through Friday. Security cameras monitor vehicles entering the zone.

Once drivers become aware of the costs, they naturally reduce unnecessary trips or travel during off-peak hours, effectively lowering congestion levels.

Criticism and Controversy

However, this policy has faced backlash for its perceived harshness. Critics argue that road pricing disproportionately affects lower-income individuals who cannot afford such fees.

Nevertheless, many countries have already implemented similar charges indirectly — for instance, through fuel taxes — though most people rarely notice.

As Turner notes:

“Road pricing can be politically and socially unpopular at first, but it remains the only solution proven to change people’s driving behavior and ultimately end traffic congestion.”